By Auria Araghi

On campus, there are only a small few who can tell about a library’s life cycle, but it’s always done with some reluctance because, if they aren’t careful breathing in before speaking, they might catch hiccups. Incidentally, a library’s life cycle and hiccups act according to the same logic. Each goes as it comes.

Before school starts, the library is a pitstop for bleary-eyed students. They’ve just plunged through the morning chill in a rush or need a place where they can hide from the rain and so shut their umbrellas before sitting motionless for a while under the heat of the lights. Librarian Ann Haber and Assistant Librarian Melissa Gilbert usually sit behind the check-out desk, or go around returning books to their shelves, likely tempering a rowdy posse of kids as they do, as all good librarians do.

The first bell cues everyone to sleepwalk out of the building, and, sooner rather than later, the only ones left are the usual suspects — those with a free period and those without one, who shuffle between the computers and printer in defiant desperation, biding time while their term papers come out double-sided or without headers or footnotes. The details don’t seem all that important, they say to convince themselves, and then they disappear.

Among the only fixtures in the library are Ms. Haber and Ms. Gilbert. Though they have the largest “classroom” on campus, they usually stay in the slightly claustrophobic space behind the check-out desk. What goes on there from 8:00 to 4:30 is a secret to most. They just work quietly, coolly, without so much as a hiccup.

The Main Campus library, the George C. Carlos Library, or just “the library,” isn’t just a library. Mr. Tad Sahara, Coach John Hurston and Ms. Connie White teach classes on the building’s upper floor — no, the high ceiling isn’t only for show. But perhaps a chandelier would be wise. Photo courtesy Auria Araghi ‘25.

The Main Campus library, the George C. Carlos Library, or just “the library,” isn’t just a library. Mr. Tad Sahara, Coach John Hurston and Ms. Connie White teach classes on the building’s upper floor — no, the high ceiling isn’t only for show. But perhaps a chandelier would be wise. Photo courtesy Auria Araghi ‘25.

As Woodward is a private school, the library exempts state restrictions on certain subject matter and so can add books according to its own selection policy. The criteria, internally published on three sheets of paper, is partly derived from the “Library Bill of Rights,” a series of principles upholding free and equal access to a library’s services as well as an obligation to include material regardless of its “origin, background, or views of those contributing to its creation.”

Another influence on selecting books comes from a theory on education originally developed by Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop, whose name has meaning only to the well-read among librarians. A professor at Ohio State University, Dr. Bishop published an essay in 1990 which analogized the role books play in children’s lives with windows, mirrors and sliding glass doors.

“Basically what she’s saying is, in a mirror, you want to see yourself reflected,” Ms. Haber said. “So what we want is… for someone to come in the library and be able to see that there’s books that reflect who they are. And then a window is to be able to look at different perspectives, sort of like through the window, observing what it must be like for somebody else. And then the sliding glass doors that you would step through into other worlds through books.”

When fitting Dr. Bishop’s ideas to a book collection as massive as Woodward’s, the librarians first have to take an audit, or a careful, nose-to-the-screen review of the material logged in their system. Then, they can decide where there’s a smudge in a mirror or fog on a window — and they’ll more or less wipe it away with their sleeves, clearing space to do work.

“You basically create a big spreadsheet, and then you go through and analyze each book in the fiction section,” Ms. Haber said. “What kind of characters does it have? What are, you know, the backgrounds of the characters? Who’s the author and are they a person of color? So we’ve tried to look at a lot of different variables.”

Recently, book publishers have been making a bigger push to diversify their output. The stories they put out and their authors are diverging faster and faster from the tradition of the classic canon, and Ms. Haber and Ms. Gilbert are keen to keep up. The main way they discover recently-published material is by prying into book review magazines. Critic recommendations in a semi-monthly publication like Kirkus Reviews or in the just-plain-monthly School Library Journal supply regular reading for them inside their offices.

“To find new titles, we like to look at School Library Journal, Kirkus, that sort of thing, and read reviews,” Ms. Gilbert said. “We like to look at award winners — basically, things that are really going to enhance our collection. You know, we want fiction that’s going to build a reader, and then information sources that are going to help their curriculum.”

English and History teachers — and especially those who teach capstones — rely on a bona fide arsenal of study resources for their students to make use of as they rout their semester projects. Before a class gathers to work beneath the looming portrait of Mr. Carlos, Ms. Haber will fill a rolling bookshelf with rows of textbooks, collections, biographies and encyclopedias, and wheel them down past the study carrels, leaving the cart near a smart board where she’ll explain citation guidelines and the curated resource page on LibGuides.

“For research, you know…it also depends on what classes are added,” Ms. Haber said. “Like, there was an African Studies class added, so I needed to bump that up. And then, for example, we had a military history class, and then it went away, and then it came back last year…. A lot of it depends on what classes are added or that come in and are looking for different topics.”

And when choosing new nonfiction for the wider curriculum, Ms. Haber first and foremost consults the Salem Press seasonal catalog, which isn’t so much sought out as it is brought to her.

The routine goes as follows: once every semester, a salesman for Salem Press will call the library landline from his and describe additions to the publisher’s list of titles. A short time after they talk, a magazine with the updated product line is sent to the school. As the librarians review it, they pay particularly close attention to those books listed under the Critical Insights series — essay writers’ bread-and-butter. Every volume–some of which concern characters in history, others a single work of literature, or else common literary themes–compiles a spate of academic essays on its topic. They function as cogs in the self-fulfilling prophecy of essay writing and perfect fodder for stray cracks in the bookshelves.

More than 14,000 spines run through the seven-story bookshelves of the library, but gaps do exist, if only in some fourth dimension underneath the shrunken paneling. If there’s a particular book, for a class or for free time, that no matter what just doesn’t come up in the academy search register, the librarians are happy to have it purchased by request. Any student, parent or teacher can send an email to either [email protected] or [email protected], or just approach the check-out desk, with a title and author.

“Anybody can give us a request, and it is in the policy,” Ms. Haber said. “We try to make sure that we, you know, honor requests. If you’ve walked in and said, ‘I’m doing a research paper on such and such,’ I try to always get at least a print book or go directly to an electronic source if we…can’t get it.”

And though it typically doesn’t end up turning into an issue, book buying is necessarily done in the shadow of the library’s budget.

In reality, the majority of spending doesn’t go towards books at all. A well-tailored host of online databases–fashioned with all the up to date accessories for archiving, research and comparative studies–is maintained not at little expense. And when considered with the costs of printers (3D and regular), recording equipment, computers and additional, cheaper items, the magnitude of the whole affair starts to be put into perspective.

“The school gives us a budget every year, and it’s, you know, a generous budget,” Ms. Haber said. “From that budget we buy all the databases, all supplies like printer ink and posters, all that stuff. Notecards, everything comes from one budget.”

A tiny portion of the budget has been eked out to go to the various displays around the library. Off against a few lucky walls dressed up in poster board and cutesy paper cutouts are tables with a selection of books correlating to some kind of timely theme. Ms. Gilbert is the arts-and-crafts mind behind these, mocking up templates on Canva and then trimming them with materials stashed in the building’s cluttered storage room.

“A lot of times I look at what the month is,” Ms. Gilbert said. “So, you know, February is Black History Month, so we want to feature black authors in our collection. And right now, I’ve got winter themed books up there because we want to, you know, just talk about seasonal reading. Who doesn’t want to read about a blizzard with a nice cup of cocoa in January?”

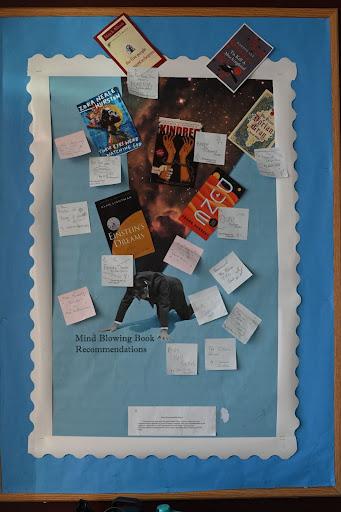

Students will stick their book recommendations to the wall, strangely all with the same handwriting… Photo courtesy Auria Araghi ‘25.

Students will stick their book recommendations to the wall, strangely all with the same handwriting… Photo courtesy Auria Araghi ‘25.

Other times, displays like the round, stepped shelving in front of the check-out desk offer a sample of the most voraciously read genres in the collection. Right now, true crime, romance and fantasy novels are what’s in — and to Laurel Wiggins ‘28, who recently picked out a short story anthology called The Collectors in the fiction alcove, it’s fantasy that’s really in. Ever since she finished her rite of passage thumbing through every page across every Harry Potter story (she considers the fourth and seventh her favorites), her feet often stay grounded in another reality.

“I think fantasy’s always been kind of cool,” Laurel said. “It’s not in our world, and, if something bad is happening here, it’s nice to escape to a different one… I don’t know, you know, flying dragons.”

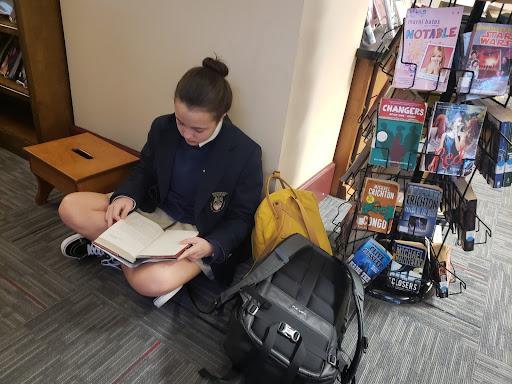

When Laurel takes trips to the library or bookstore, she’ll browse around for a fantasy or science fiction novel and then drop down to a handy spot on the floor. Here pictured in the library, she’s reading The Collectors, a collection of young adult fiction which won the 2024 Michael L. Printz award. Beside her is a book rack carrying older, yellowed paperbacks. Photo courtesy of Auria Araghi ‘25.

When Laurel takes trips to the library or bookstore, she’ll browse around for a fantasy or science fiction novel and then drop down to a handy spot on the floor. Here pictured in the library, she’s reading The Collectors, a collection of young adult fiction which won the 2024 Michael L. Printz award. Beside her is a book rack carrying older, yellowed paperbacks. Photo courtesy of Auria Araghi ‘25.