By Auria Araghi

“The news” as it’s happening sticks to more than just a moment in time — any conflict, election or controversy packs context. This year’s election, for example, carries its load of precedents: analysts gauge four years of dense history, what’s changed, attitudes towards major issues… the election is full of “firsts,” so it’s been said, but we can make slight sense of them because they’ve built over time. If metaphors help, we haven’t been put through some scientific experiment that’s zapped us forward four years — we haven’t skipped to a book’s climax, rather having slogged through the setup.

In the last four years, and in the four year intervals starting from 1789, the election news became a fixture alongside print papers, TV, smartphone notifications, you-name-the-rest, and in the four year intervals dating back to Caesar or no?, we’ve taken sides. So in search of answers for our “firsts”, we obviously ought to be asking questions worthy of our satiric, this-again? history: How did we get here? Have we been here before? — if not — Oh, gosh! — if so — Oh, gosh! But before all that, we should first ask, Where on Earth are we? If we were asking questions so broad, the appropriately offish answer to the last one would go, On Earth, of course — but if we were asking broad questions, everybody knows we did so hoping for something specific.

After Caesar’s assassination, Augustus fronted an uncomfortably volatile political state. Taking due autocratic precautions, he outlawed spoken and written criticisms against the ‘Empire so as to unite Roman opinion and secure his position. Augustus never asked, Where on Earth am I?, most likely because he held every confidence he stood above it, but he must have wondered at least once, How did I get here? To answer, How did Augustus get there? — we know better than him! “Context” from a while ago is just “history.”

Context from a week ago is history being made. Our lives make up the back pages of textbooks which haven’t been published and the front pages of websites to become unrecognizable after a refresh, and speaking to the latter, maybe our syncopated attentions put us on a treadmill, virtually leading us in loops, marking time — actually taking us to where we’ve been.

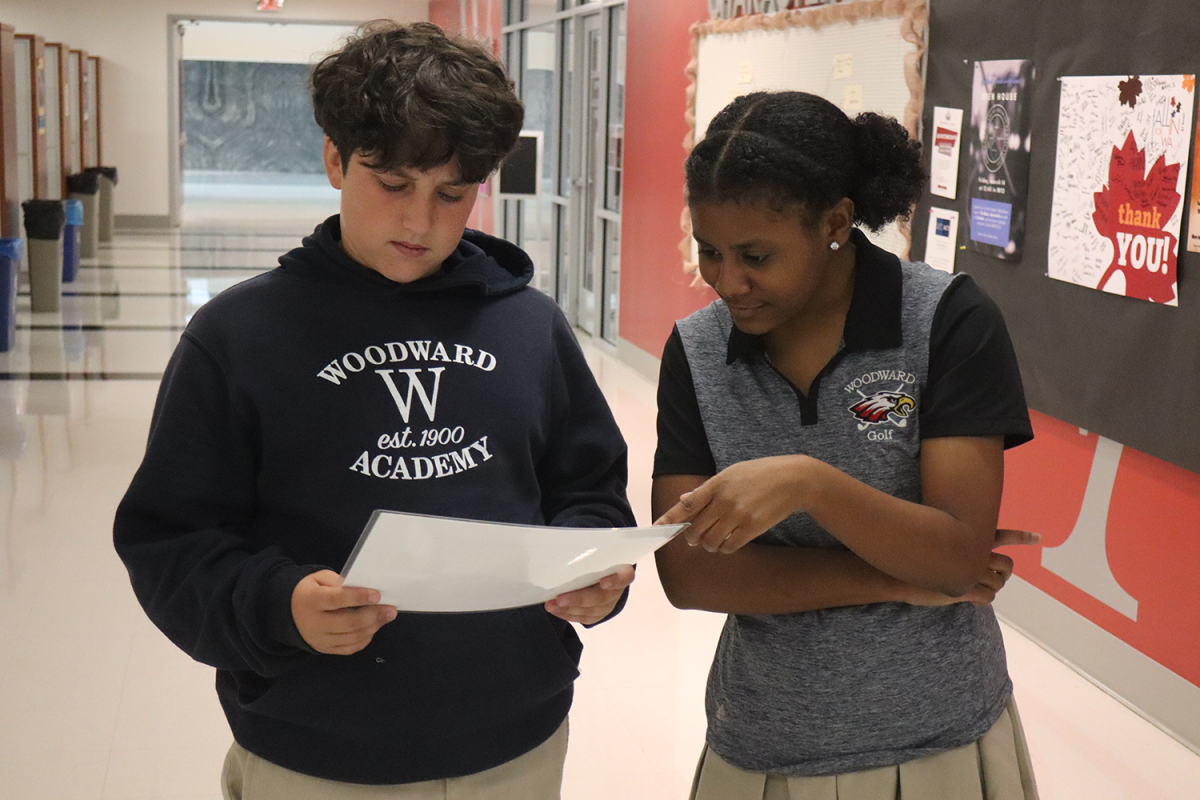

Ms. Maggie Berthiaume, who goes by Ms. B, is not a history teacher, but she does direct the Upper School debate program. When her students debate an issue, they make use of historical precedent and recent developments as evidence. The recent issues usually don’t spring from nowhere, but from trends reaching a head.

“So one of the things that I think is really important is to try and get a big picture of the issues,” Ms. B said. “If you’re interested in learning about Israel, Palestine, don’t read, you know, the minute-to-minute-what’s-happening-on-the-ground tactical stuff. Read the history of Israel and Palestine to give you context… that then gives you the ability to read those minute-by-minute articles and understand what’s going on.”

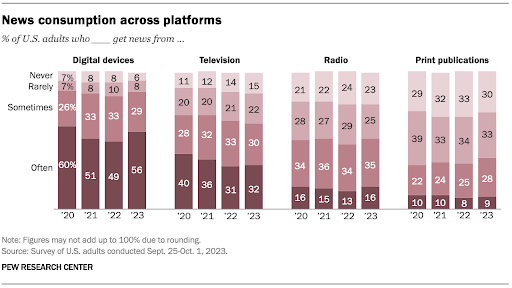

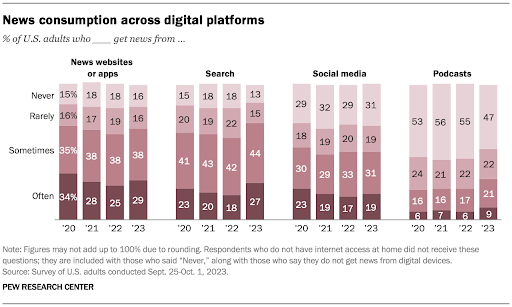

Most Americans get their news online, specifically (or more broadly) news from digital newspapers, outlets, Google searches and social media. There’s debate on whether social media curates “echo chambers” that augment polarizing opinions: on the one hand, algorithms refrain from challenging users, who might click off otherwise, especially considering the social milieu that doesn’t always distinguish offense from dissent. To flip the coin, dissent has never been so convenient; social media hosts the ideological extremes and the purgatories in between. Contentious posts are popular posts, spreading beyond a “demographic,” so to internet-speak, by merit of their pop-up pop-cultural relevance. And is it unfair to call breakout posts, polemic or not, pop culture? Probably. To take the symbolic coin and turn it over again under your palm, notice your own social media “neighborhood,” so to Mr. Rogers-speak, and think if by staying there you hear the news in ways that are more personal than they are professional.

“The journalist and your mom’s coworker are given the same level of credibility,” Ms. B said. “I think that’s why it’s really important to try and find the people who are the experts in the field and who have been doing it for a really long time rather than the person who, like, just got excited about this issue. So it doesn’t mean that that person is necessarily wrong, but they’re more likely to be wrong than somebody who’s been studying.”

Where we learn the news. Screenshot courtesy Pew Research

Gloria Mark and her team of stopwatch-experts timed the intervals at which people complete work, from the moment they open a document until they stopped typing, for a testing period of over a decade. Pass 14 years, and people held onto their sentences for shorter…and shorter…and shorter periods of time. You probably know, but our attention spans are adapting to the new, hustled norm. Maybe more usefully, we tend to engage in “rote activity,” or periods when whatever we’re doing doesn’t challenge us much or keep us attentive. Mrs. Lori Fenzl teaches her Government students to stay critical, and when class starts she has them listen to that day’s CNN 10, a ten minute video (give or take a second) that collects the recent Big News. She noted how social media changed the ways her students might interact with the headlines.

“I could get on TikTok and start announcing the news,” Mrs. Fenzl said. “I don’t know why you would believe me. I don’t have the background, I don’t have the sources… I could just literally be repeating whatever somebody says, and I think that’s the fundamental problem… and I think that’s part of the news problem that we’re facing right now.”

And you can pick at sources all you want, but some problems run inwardly: “confirmation bias” is tough to catch — when the news tells us what we want to hear, our critical muscles ease up. Enough repetition, and the words slide by scot-free. Checking ourselves and differentiating “listening” from typical “rote activity” will hold us to the same standards as our sources and, in the long term, develop fainter biases for them to conform to.

(Because we air towards optimism.)

“I think there’s something that most people don’t like to admit, but it’s confirmation bias,” Mrs. Fenzl said. “And the way that I read my news versus the way you read your news, I’m going to tend to agree with whatever I already agree with. And I know that sounds very simplistic, but when we read the news or listen to the news, we nod our heads and agree with something. We go ‘Yes, absolutely, that’s right,’ when the other person sitting next to me that might have a different belief system or a different value about that particular event that news, they’re going, ‘Why are you nodding your head? What are you – what are you doing?’”

(Most) Journalists are only human, and, while articles might drone in their monotone way, biases are human, too. Like a collage, snapshots of truth may piece-by-piece intimate a story; good-faith reporting sets out to keep all the pictures high-definition and leave ample room for interpretation, or what we make of the facts. It’s really a bit artsy. Yet, artists might try to steer through negative space: the absence of information can influence us just as much as any damning tidbit.

“I think that [identifying absence] would come with experience, quite honestly,” Mrs. Fenzl said. “I would say as a high school student, I definitely didn’t have enough background knowledge to maybe catch some of these nuances. Possibly being a little more jaded…the more you realize that ‘Okay, there’s bias there.’ I see it, but I’m still listening to it because I’m trying to just get the information.”

Part One – this is Part Two!