Working Alone Together | Anna Schwartz ’24

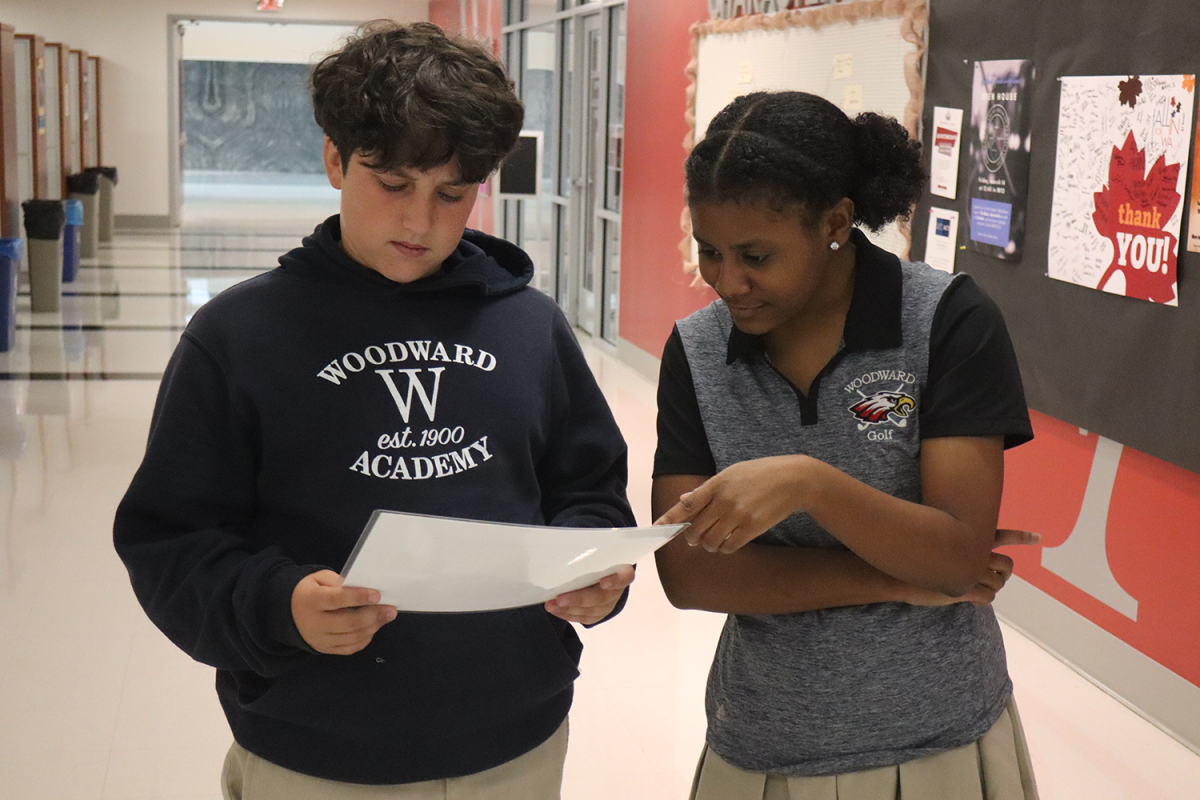

I was slightly confused but too shy to clarify when my neighbors requested that I encourage parallel play between her two children. Babysitting does not usually require deep study of modern developmental philosophy, so I meekly nodded my head and resolved to rely on Google once they had left for their date night. I suppose new parenting methods are of great importance to the parents themselves, but I never would have suspected that babysitting a pair of infants could expand my idea of success in the real world. According to everyone’s favorite and faithful web browser, parallel play is a behavior observed and fostered in toddlers. While engaging in parallel play, each child occupies themselves individually while staying close together and sometimes mimicking each other. Without any prompting on my part, the kids I was looking after resorted to separate amusement with occasional, always pleasant interaction. Growing up with my sister, we would either play together or play against each other. Dolls and dress-up were collaborative experiences, but board and card games were always a competition. Being equally strong spirited and very close in age, both types of activities usually ended in a fight. As teenagers, spending time with my sister is much less violent and aggravating. We will either work on separate assignments, do fun art projects, or even cook our meals together while listening to a playlist from our shared Spotify accounts; we subconsciously utilize parallel play. Similarly, my classmates and I are rarely assigned tedious group projects anymore; if we work together it is by choice. Because our elementary experience was so collaborative, we do not hesitate to ask each other for help. Even though special awards and honors have always been given at my school, class rankings and other direct forms of competition are subtle or undetectable. Due to the environment that these regulations create, I can survive stressful situations without injuring the friendships I make along the way. In infants, high schoolers, and even adults, individual achievement and compassion should be emphasized over their respective underlying principles of competition and collaboration.

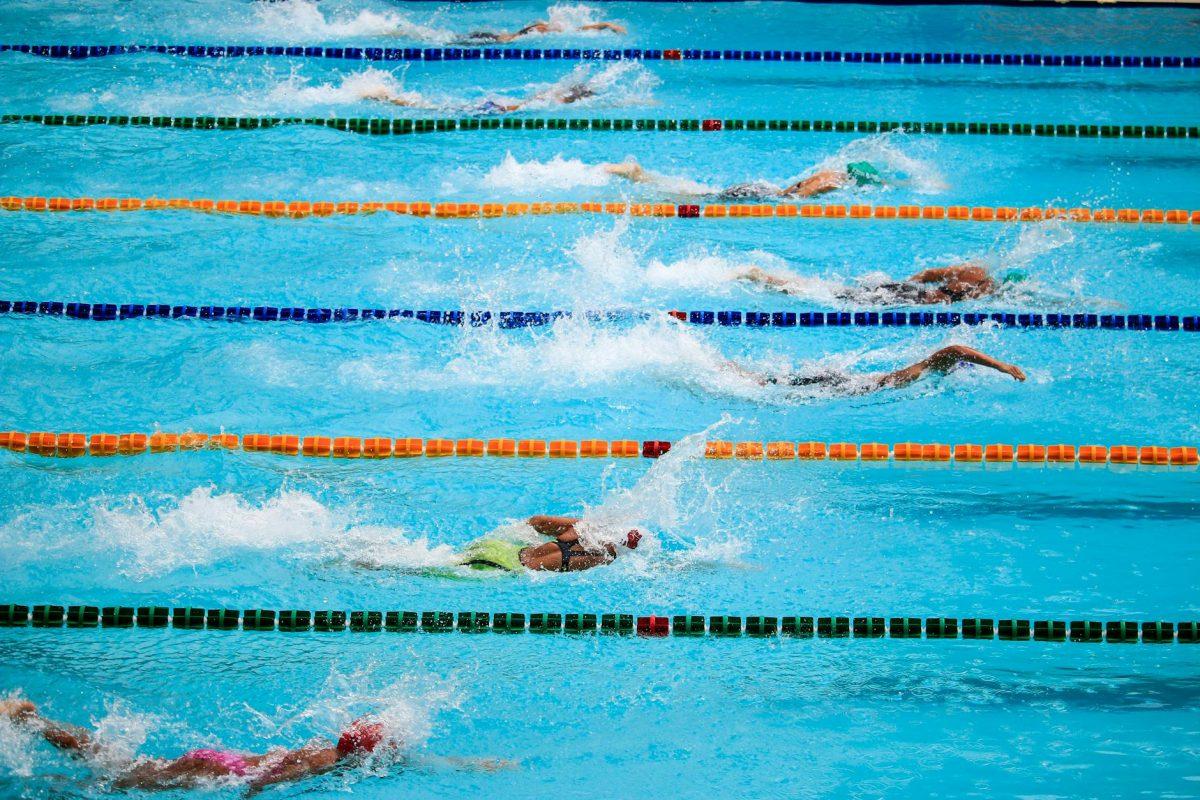

Despite competition’s suspected ability to motivate, it has great potential to harm developing children and working adults alike. In general, some friendly competition increases work ethic. Vying for a promotion might convince someone to work a little overtime, and the possibility of winning a state tournament can persuade a high school athlete to consistently practice. By rewarding the best, competition gives people a reason to become the best version of themselves. When their success is validated, it encourages them to continue on their path of achievement. However, the dangerous toxicity of overly competitive environments has serious and lasting effects. The classic strict parents who require perfect test scores and blue ribbons produce isolated adults with anxiety and low self worth. These formerly pressured children may resent their upbringing, or in some cases, they may appreciate its ultimate benefits and raise the next generation in a similar manner. Sometimes, when mixed properly with tenderness and care, high expectations lead to confident and motivated individuals fully prepared for the ups and downs of adult life. Although competition and goals alone can sometimes encourage markings of greatness, true greatness needs no encouragement. The real greatness lies in the passion and determination required to reach one’s goals. Beyond the toxic environments that competition feeds, the key symptom of the illness of competition is valuing conformity over individuality. High school tends to encourage “fitting in” over standing out, but this principle does not need to extend out of social life and into academics. A beloved quote dusted off to comfort the artists and athletes of the world comfortingly reminds us that “everyone is a genius, but if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.” This pearl of wisdom is frequently misattributed to Albert Einstein, a great competitor and collaborator, but this exact quote actually originates from a cheesy early 2000s facebook post, and the true origin of the sentiment is still heavily debated. One might brush off this mistake as an embarrassing misstep, but I find it enlightening that we would rather be lied to in order to believe something encouraging than fathom that someone who isn’t a winner could be an inspiration. High school can feel like a forest of fishes in trees because certain skills and victories are valued over others. The birds and monkeys of a subject will receive constant validation because they continue to win, but this encouragement is not extended to the animals left on the forest floor. Competition can be a healthy motivator only if it is utilized properly. Usually, competition emerges on its own and does not need to be highlighted, especially not with teenagers in all of their hormonal vulnerability.

As opposed to the competitive lifestyle of my parent’s generation, my generation likes to proclaim collaboration as the all important life skill to be taught and fostered throughout one’s education. Sure, there are obvious benefits to collaborating, but I know we have all had collaborations turn into more work for one person and a free pass for the rest. The American school system focuses on reminding us that learning to work together makes us more considerate, develops friendships, and fine-tunes our patience and politeness. Collaboration can sometimes yield better and more thorough work. The combination of two or more minds can lead to new discoveries and increased creativity. For an example of the positive effects of working together, look back at the facebook-born analogy of the tree. Given that the fish’s skill set is not catered to the task ahead, a bird could pick it up and fly it to the top of the tree, or it could ride on the monkey’s back. Of course this is not a perfect way of thinking of things because the fish would quickly die without oxygen from water, but in the end everyone makes it to the top. Later on, maybe the fish will teach the other animals to swim (just kidding, but not really). Either way, collaboration seems more useful than leaving others behind. However, forced collaboration is not the only or best way to uplift a community. Those without particular skills may become reliant on others and unable to work alone. In the real world, collaboration tends to take place after a great deal of individual effort. Combining efforts after everyone has tried for themselves is a great strategy to avoid losing possible ideas along the way. Additionally, having individual goals does not stop people from collaborating. I often find myself asking my friends for help with my math work, but I return the favor by checking over their essays. In this way, we all develop both the actual life skills and the interpersonal skills we need to have a fulfilling and successful adult life. Although group projects can be a massive pain, I understand now that the forced collaboration of elementary school has made me comfortable enough to collaborate by choice at a higher level. However, teenagers do not have to be reminded of the benefits of working together; they need to learn from their mistakes to be less stubbornly independent and reach out for help.

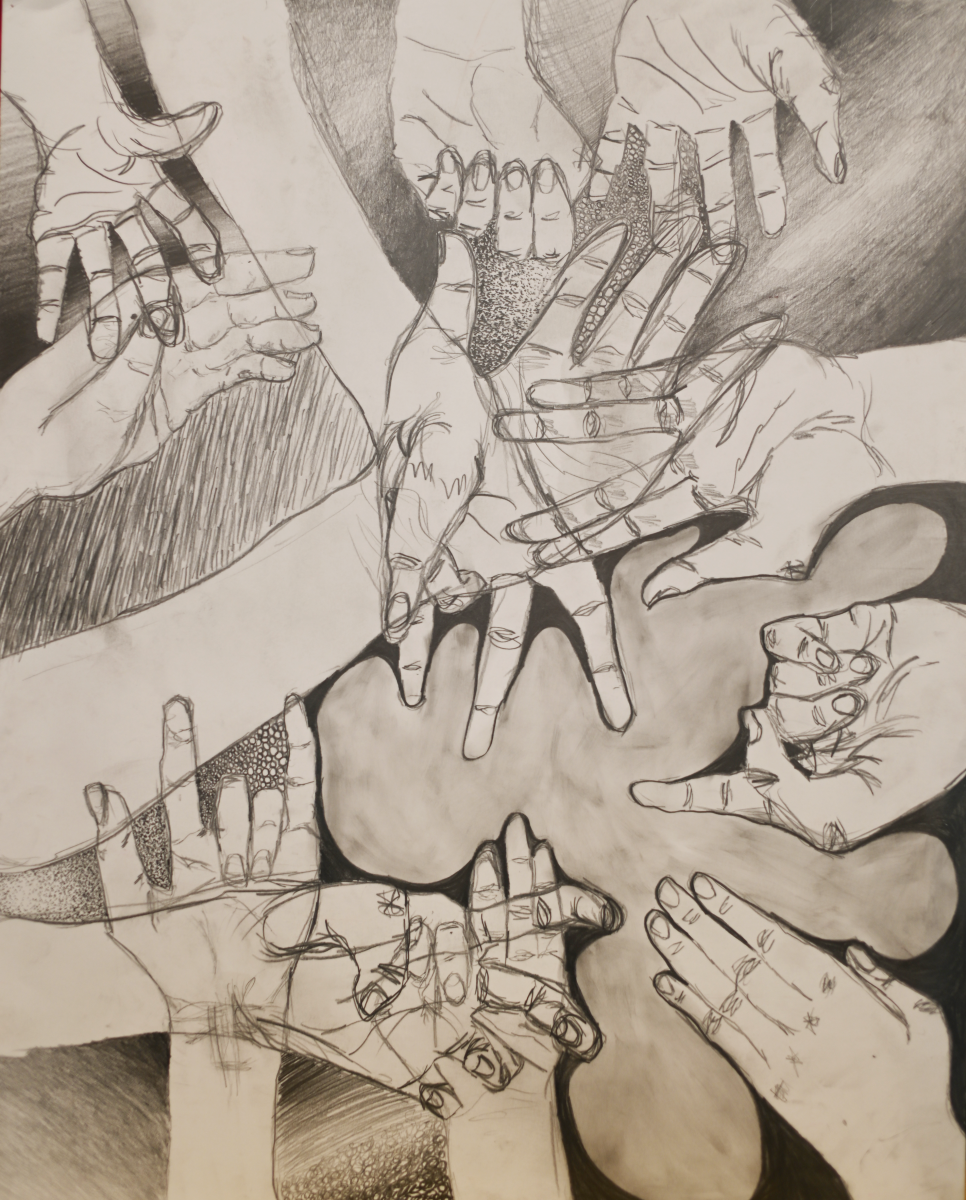

Both competition and collaboration are natural human impulses that should be encouraged in young children, but once learnt, requiring high school students to participate in either creates toxic environments. For those of us already put in the boxes of either competition or collaboration, emphasizing individuality and compassion will steer us towards healthier goals. Imagine if we could all learn to use parallel play; each diligently working on our own and occasionally giving or receiving ideas. A basketball player will benefit from trying to be a more accurate shooter than his teammate, but he should also know when to pass the ball and let someone else take the shot. Furthermore, a team of players with exactly the same skills would not work efficiently, so players should not try to mimic each other. Most importantly, a team member should be kind to his teammates because without compassion, there is no collaboration. Instead of reinforcing natural instincts, high schools should provide students with the methods needed to put those instincts to good use.